Key Takeaways

- Ukiyo-e means "pictures of the floating world" and originated in Japan's Edo period (1603-1868)

- Master artists like Hokusai and Hiroshige created iconic works that influenced Western art movements

- The collaborative process involved four specialists: publisher, artist, carver, and printer

- Japonisme movement brought ukiyo-e techniques to Impressionist masters like Van Gogh, Monet, and Degas

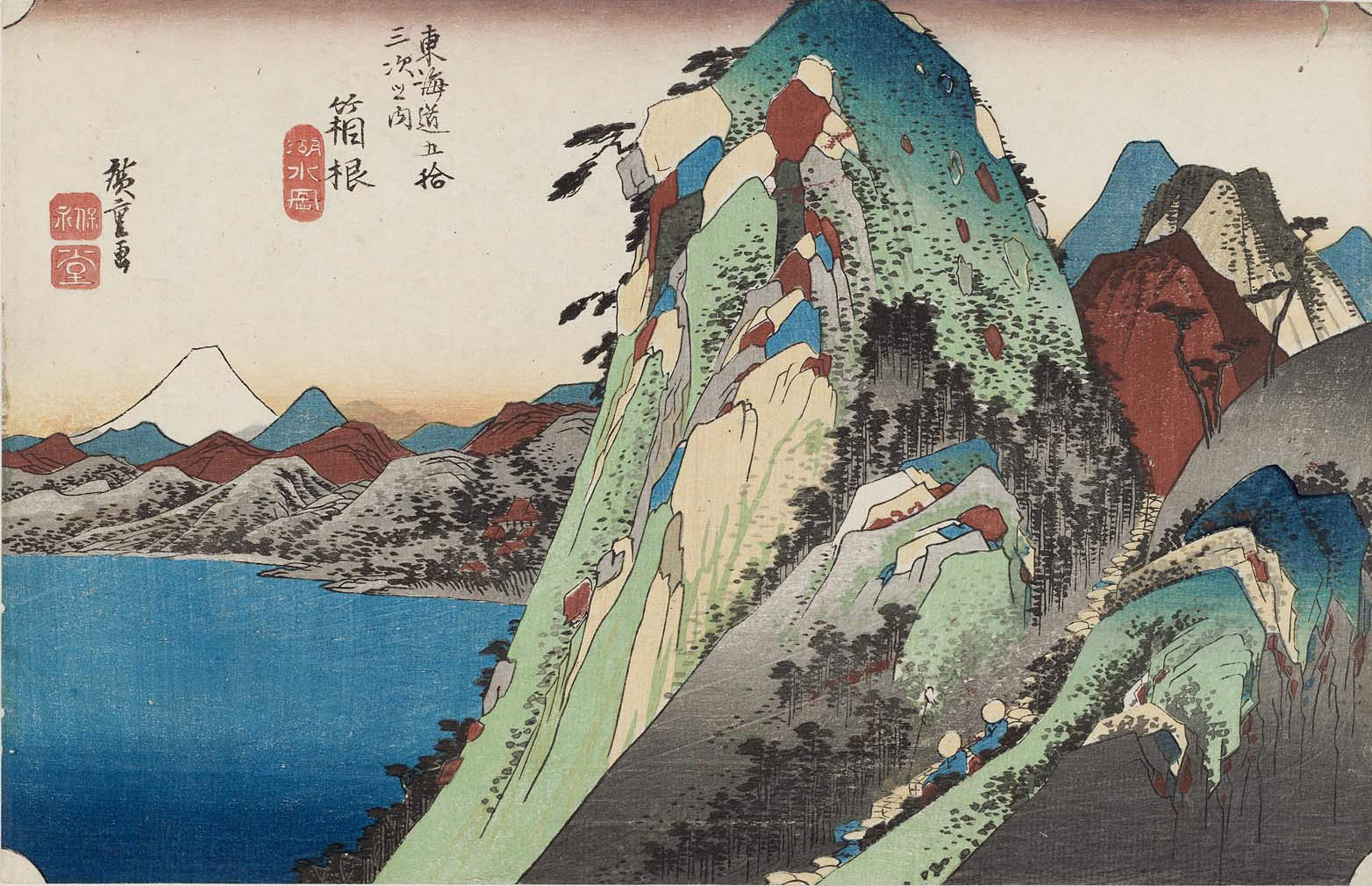

- Common themes included kabuki actors, courtesans, landscapes, and everyday life scenes

Traditional ukiyo-e print showcasing the vibrant world of kabuki theater and seasonal beauty

Definition & Origins

Ukiyo-e literally means "pictures of the floating world" in Japanese. During Japan's Edo period (1603-1868), the term "floating world" referred to the licensed pleasure districts of major cities where entertainment, fashion, and hedonistic culture flourished. These areas became the playgrounds of the newly wealthy merchant class, featuring geisha houses, kabuki theaters, and fashionable establishments.

Originally, the concept of ukiyo expressed the Buddhist idea of life's transitory nature. However, during the prosperous Edo period, this pessimistic notion transformed into a celebration of living in the moment and enjoying life's pleasures. Artists began depicting scenes of courtesans, kabuki actors, and everyday urban life, making these images accessible to the general public through affordable woodblock prints.

The collaborative ukiyo-e production process in a traditional Edo-period workshop

The Manufacturing Process

Each ukiyo-e print was created through the collaborative effort of four skilled individuals: the publisher, artist, carver, and printer. This teamwork, known as the "ukiyo-e quartet," was essential to producing the thousands of prints that flooded Japan's markets.

The Four-Stage Production Process

- Design Phase: The artist sketched the design on paper with brush and ink

- Carving Phase: The block cutter carved the design into cherry wood blocks

- Color Planning: Additional blocks were created for each color needed

- Printing Phase: The printer applied pigments and pressed paper onto blocks

The introduction of full-color printing (nishiki-e or "brocade pictures") in 1765 revolutionized the art form. This technique used registration marks—small rectangles cut into each block—to ensure perfect alignment when printing multiple colors on a single sheet.

Visual guide to the traditional ukiyo-e printing process from sketch to finished print

Major Artists & Examples

The golden age of ukiyo-e produced legendary masters whose works continue to captivate audiences worldwide. These artists elevated woodblock printing from commercial craft to high art, each contributing unique styles and innovations to the medium.

Katsushika Hokusai (1760-1849)

Perhaps most famous for "The Great Wave off Kanagawa", Hokusai transformed landscape printing with his "Thirty-six Views of Mount Fuji" series. His innovative use of Prussian blue and dramatic compositions influenced countless Western artists, including Claude Monet, who displayed Hokusai's prints in his Giverny home.

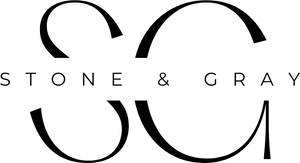

Utagawa Hiroshige (1797-1858)

Known as the last great master of ukiyo-e, Hiroshige's landscape prints featured innovative techniques like bokashi (gradation) and captured atmospheric effects like rain and snow. His "One Hundred Famous Views of Edo" series provided intimate glimpses of daily life in Japan's capital.

Key Artists Timeline

- Suzuki Harunobu (1725-1770): Pioneer of full-color printing (nishiki-e)

- Kitagawa Utamaro (1753-1806): Master of bijin-ga (beautiful women) portraits

- Tōshūsai Sharaku (active 1794-1795): Revolutionary kabuki actor portraits

- Utagawa Kunisada (1786-1864): Prolific artist with over 20,000 designs

Diverse themes of ukiyo-e: from elegant courtesans to dramatic kabuki actors and serene landscapes

Major Themes & Subjects

Ukiyo-e encompassed a rich variety of subjects that reflected the interests and concerns of Edo period society. These themes evolved from early depictions of pleasure quarters to encompass landscapes, literature, and contemporary events.

Bijin-ga (Beautiful Women)

Portraits of courtesans, geisha, and fashionable women formed a central theme of ukiyo-e. These prints showcased the latest fashions, hairstyles, and accessories, serving as both art and fashion magazines for their time.

Yakusha-e (Actor Portraits)

Kabuki actors were the celebrities of Edo period Japan, and their portraits were extremely popular. Artists like Sharaku captured actors in dramatic poses and expressions, often emphasizing their individual characteristics and personality.

Fukei-ga (Landscape Pictures)

Landscape prints gained prominence in the 19th century with masters like Hokusai and Hiroshige. These works often featured famous scenic spots, seasonal changes, and travel destinations along Japan's well-developed road network.

Cultural Insight: The popularity of landscape prints coincided with increased domestic tourism during the peaceful Edo period. Travelers purchased these prints as souvenirs of famous locations, similar to modern postcard collecting.

Ukiyo-e style map depicting the bustling urban landscape of Edo period Japan

Western Influence & Japonisme

When Japan opened to international trade in 1854, ukiyo-e prints began flowing into European markets, sparking an artistic revolution known as Japonisme. Western artists were captivated by ukiyo-e's bold compositions, flat color planes, and unconventional perspectives.

Impact on Impressionism

Artists like Monet, Van Gogh, and Degas collected hundreds of ukiyo-e prints, incorporating their techniques into Western painting. The Japanese approach to composition, with its emphasis on asymmetry and negative space, fundamentally changed how Western artists viewed pictorial space.

Key Japanese Techniques Adopted by Western Artists

- Asymmetrical Composition: Breaking away from classical Western symmetry

- Flat Color Planes: Eliminating traditional chiaroscuro and modeling

- Cropped Figures: Using unusual viewpoints and partial figures

- Bold Outlines: Emphasizing contour lines over volume

- Decorative Patterns: Integrating ornamental elements into fine art

Contemporary interior showcasing the enduring appeal of ukiyo-e in modern design

Modern Legacy & Contemporary Relevance

Ukiyo-e's influence extends far beyond its historical period, continuing to shape contemporary art, design, and popular culture. Some art scholars consider ukiyo-e the "father" of modern Western art, recognizing its fundamental role in the development of modernist movements.

Contemporary Applications

Today's graphic designers, animators, and digital artists frequently draw inspiration from ukiyo-e principles. The bold graphics, simplified forms, and dramatic compositions pioneered by Japanese printmakers remain relevant in modern visual communication.

Modern fashion integrating traditional ukiyo-e elements with contemporary design

Glossary of Key Terms

Bijin-ga: "Pictures of beautiful women" - portraits of courtesans, geisha, and fashionable ladies

Bokashi: Gradation technique created by hand-inking wet woodblocks

Eshi: The artist who designed the prints

Hanmoto: The publisher who coordinated and financed production

Horishi: The skilled craftsman who carved the woodblocks

Japonisme: Western artistic movement influenced by Japanese aesthetics

Nishiki-e: "Brocade pictures" - full-color woodblock prints

Surishi: The printer who applied colors and created final prints

Ukiyo: "Floating world" - the pleasure districts and entertainment culture of Edo period Japan

Yakusha-e: Portraits of kabuki actors in theatrical roles

Discover Japanese-Inspired Art for Your Space

Bring the timeless beauty of Japanese artistic traditions into your home with our carefully curated collection of prints inspired by the rich heritage of ukiyo-e and Asian art.

Educational Disclaimer

This article is for educational purposes only. Images and historical facts are drawn from well-regarded art history sources including The Metropolitan Museum of Art, Victoria & Albert Museum, and Library of Congress. For purchase of ukiyo-e inspired prints and Japanese art, please visit our collection.

Last Updated: September 8, 2025 | Sources: Metropolitan Museum of Art, Victoria & Albert Museum, Library of Congress, Asian Art Museum, and academic art history publications